Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

Tom Stoppard once described his artistic goal as follows:

I realized quite some time ago that I was in it because of the theatre rather than because of the literature. I like theatre, I like showbiz, and that’s what I’m true to…. I’ve benefited greatly from Peter Wood’s [a London theatre director] down-to-earth way of telling me, ‘Right, I’m sitting in J16, and I don’t understand what you’re trying to tell me. It’s not clear.’ There’s none of this stuff about, ‘When Faber and Faber bring it out, I’ll be able to read it six times and work it out for myself.’ (Quoted Hayman, p. 8)

Some of us are drawn to solving play-puzzles, so I hope that this introduction to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (which I confess, I have read at least six times) proves helpful. This is an honest, and funny play. Stoppard brilliantly revisits Shakespearean notions of life and death. (more…)

Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night

References in this discussion are to the Penguin edition of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, edited by M. M. Mahood and introduced by Michael Dobson (1982).

TWELFTH NIGHT: COMPOSITION

Harley Granville Barker, a leading twentieth-century theatre producer and writer, refers to Twelfth Night as “the last play of Shakespeare’s golden age,” which he probably wrote in late 1601 or early 1602. Shakespeare was then thirty-seven and at the height of his popularity as a playwright. Twelfth Night is often regarded as the culmination of his comic writing for the stage. It followed a series of comic “hits,” made up of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595), The Merchant of Venice (1596), the Falstaff scenes in Henry IV (1596-1598), Much Ado about Nothing (1598), and As You Like It (1599-1600).

For Twelfth Night Shakespeare drew on Barnaby Riche’s prose romance, Apolonius and Silla, in Riche His Farewell to Militarie Profession (1581); on three sixteenth-century Italian comedies entitled Gl’Ingannati and Gl’Inganni (“The Deceived”); and/or on on French adaptations of these. His ultimate source was the Menaechmi, a farce about identical twins by the Roman playwright Plautus, a work which he had adapted once before in The Comedy of Errors (1594).

The script survives as one of eighteen plays not published in Shakespeare’s lifetime but included seven years after his death in the collected edition known as the First Folio (1623). You can view a facsimile of the Twelfth Night title page in the First Folio at https://www.folger.edu/twelfth-night [left]; or at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Twelfth_Night_F1.jpg

A FUNNY PLAY

I first studied Twelfth Night in high school, at a time of life when I dreamed deliciously over the romance and collapsed into helpless giggles at the comedy. Though so many years have passed since then, I know that I still haven’t penetrated the play’s depths of meaning. However, perhaps in the hope of understanding, I’ve always treasured the Oxford student edition (1959) that we used as teenagers. The editor, George H. Cowling, explains Twelfth Night’s unique appeal:

[Shakespeare] did not merely scoff at folly: he wisely knew that mankind is imperfect, and that people, even the wisest of men, are not entirely creatures of reason….He found men a little less than angelic, but was content to have them so. And so he laughed at affectation and egoism, not merely with the rational intellectuality of the satirist, but with delight, because human nature is what it is.

Shakespeare was never more romantic, more comic, more wise, than in Twelfth Night. Each of Shakespeare’s comedies has its own beauties; but for wit and humour (and surely it is the function of a comedy to be comic) this in my opinion is the best of them all. (pp. 19-20)

Forty years later, Harold Bloom recorded a similar response:

Despite my personal preference for As You Like It, which is founded upon my passion for Rosalind, I would have to admit that Twelfth Night is surely the greatest of all Shakespeare’s pure comedies….I think the play is much Shakespeare’s funniest. (Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. London: Fourth Estate, 1999: 226; 228)

Bloom further contrasts the directness of Twelfth Night with Shakespeare’s problem comedies such as Measure for Measure (1603), and late romances such as The Winter’s Tale (1609) and The Tempest (1611).

STUDY EXERCISE ONE: THE SETTING OF TWELFTH NIGHT

Michael Dobson describes Illyria as “this self-indulgent lover’s territory” (Introduction xxii). He points out: “we find ourselves in Illyria at the outset, and we stay there…the world beyond comes to us as nothing more substantial than a succession of rumours” (xxiii); and that for both Viola and Sebastian “getting washed up on Illyria may turn out to be rather like dying and going to heaven” (xxiv). “Illyria is a sunlit never-never land of love and poetry, outside the ordinary historical time in which we mere mortals are trapped” (xxiv). However, “the choice of Illyria as a setting places love and escapism alongside danger and death” (xxvi).

How far do you agree with the various parts of Dobson’s account of Illyria?

Which features (if any) of the account seem inappropriate to you?

In your view, what further features of Illyria (if any) are worthy of attention?

The first documented performance of Twelfth Night took place on 2 February 1602, at Candlemas, the Church’s feast celebrating the baby Jesus’ Presentation in the Temple. Shakespeare’s company, the Chamberlain’s Men, performed before an audience of law students and lawyers in the Middle Temple Hall, one of the Inns of Court (law colleges) in central London. John Manningham, a barrister, noted in his diary his pleasure at the gulling of Malvolio.

The title, “Twelfth Night,” nevertheless refers not to Candlemas but to the Feast of the Epiphany, which always falls twelve days after Christmas and commemorates the Wise Men’s “epiphany,” or sight of the Christ Child.

EARLY PERFORMANCES

In The First Night of Twelfth Night (London, 1954), Leslie Hotson argued contentiously that the play’s first performance in fact took place at the royal court’s Epiphany celebration, on January 6, 1601, when Don Virginio Orsino, Duke of Bracchiano, who visited Elizabeth’s court in 1600-1601, was in the audience. Despite these associations with the Church calendar, Twelfth Night is not a religious play, unless you consider optimism and joy to be religious feelings.

Shakespeare seems to have designed Twelfth Night for transport between professional staging at the Globe Theatre, which was the home of the Chamberlain’s Men from 1599, and amateur venues like colleges and great halls. In contrast with many of Shakespeare’s plays, performance does not require an upper stage. The two upstage entrances in the public theatre or a great hall could stand for Orsino’s and Olivia’s houses, while a central inner stage or an onstage tent might be Malvolio’s prison. A few judicious words at the beginning of scenes and elsewhere transmute the central playing area—the apron stage in the public theatre—from the sea coast of Illyria, to either of the noble households, to the route between them, to a city street. This fluidity of locale encourages speedy scene changes and a fast-flowing, lively presentation. (See further, Michael Dobson’s discussion of “The Play in Performance,” Penguin Edition, lxiii-lxx.)

GENRE

A. Festive Comedy

In Christian Europe, Christmas and the Feast of the Epiphany are winter solstice festivals corresponding with the ancient Roman festival of the Saturnalia, “a period of general festivity, licence for slaves, giving of presents, and lighting of candles” (OCCL). The Saturnalia takes its name from the Italian agricultural deity, Saturn (Greek Chronos). It originally celebrated the sowing of crops in preparation for spring. Both the pagan and the Christian festivals celebrate the turning of the earth away from winter, toward the light and warmth of the sun.

In Shakespeare’s England Christmas revelry reached a peak on Twelfth Night, which was the last day of the holidays. Activities included feasting, drinking, games, joking, riddles, music, dancing, the singing of catches and rounds, and, as in the Saturnalia and the preceding medieval Feast of Fools, a reversal of roles between servants and masters. The term, “Twelfth Night,” does not occur in Shakespeare’s text, but What You Will, the subtitle in the First Folio, captures the spirit of the Saturnalia and its Christian successors: “The sanguine Will [Shakespeare] gives us What You Will” (Bloom 229). In 1958 L. G. Salingar wrote in fact that “the thematic key” to Twelfth Night was its “imitation of a feast of misrule, when normal restraints and relationships were overthrown”:

The subplot shows a prolonged season of misrule, or ‘uncivil rule,’ in Olivia’s household, with Sir Toby turning night into day; there are drinking, dancing, and singing, scenes of mock wooing, a mock sword fight, and the gulling of an unpopular member of the household, with Feste mumming it as a priest and attempting a mock exorcism in the manner of the Feast of Fools…Moreover this saturnalian spirit invades the whole play. In the main plot, sister is mistaken for brother and brother for sister…. (“The Design of Twelfth Night.” Shakespeare Quarterly 9 (1958): 118 (117-139)

L. Barber’s Shakespeare’s Festive Comedy (Princeton, 1959), described by Michael Dobson in the introduction to the current Penguin edition as “possibly the most influential book on Shakespearian comedy of the last half century” (lxxii), expounded Salingar’s insight from an anthropological perspective: “[Twelfth Night],” Barber wrote, “is filled with the zany spirit of twelfth night.”

STUDY EXERCISE TWO: THE FESTIVE ORIGINS OF TWELFTH NIGHT

Investigate Salingar’s reference to “a mock exorcism in the manner of the Feast of Fools.” (See M. M. Mahood’s Introduction to the earlier Penguin edition of Twelfth Night p. 14. For an exhaustive account of the Feast of Fools, see E. K. Chambers, The Medieval Stage. Vol. I, Chapters XIII, XIV and XV. London, 1903, often reprinted).

Where does the exorcism occur in Twelfth Night? Who is the exorcist, and who or what does he cast out?

Find examples of drinking, feasting, music, dancing, singing, riddling, joking, and mumming (play-acting, usually involving masks or disguises) in your text of Twelfth Night.

How do these features affect the comedy’s overall mood?

B. Gentle Melancholy

On the other hand, mainly through Feste, whose songs delight both his on-stage and off-stage audiences, Twelfth Night oversees the disorderly fun and “misrule” from a sweetly melancholic perspective which reminds us of the fleeting quality of youthful love and joy. This context makes the comedy’s music and dancing, feasting and romance, gender-bending and reversals of hierarchy seem all the more precious by contrast. For Shakespeare’s early audiences, twelfth night was not only the most boisterous day of the holidays—it was also the last. The play’s ending accordingly captures a feeling of the carnival being over. Tomorrow the workaday world of toil and domination, of marriage and responsibility, of sadness, old age and death, will re-constitute itself. Lovers and merry-makers alike will return to their economically and socially determined places and functions—“For the rain it raineth every day.”

C. Satire

The hidden heart of Twelfth Night lies in Shakespeare’s seriocomic rivalry with Ben Jonson, whose comedy of humours is being satirised throughout….Shakespeare generally mocks these mechanical operations of the spirit, his larger invention of the human scorns this reductiveness. (Bloom 228)

Bloom compares the theory of the humours to popular psychology today. The humours were certainly a fashionable interest in the period when Shakespeare was writing Twelfth Night. In fact Shakespeare himself is listed as “a principal comedian” for the first performance, by the Chamberlain’s Men in 1598, of Ben Jonson’s popular play, Every Man in His Humour:

Medieval medicine associated physical and mental dispositions with the preponderance of certain humours in the body: blood (hot and moist), phlegm (cold and moist), yellow bile (hot and dry) and black bile (cold and dry) should blend equally in the body. Imbalance led to various kinds of distempers. The theory became more and more complex, and the most elaborate account is to be found in Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (first published 1621), by which time, however, medicine had begun to discountenance the theory.

(Martin Seymour-Smith, ed. Ben Jonson. Every Man in His Humour. London: Ernest Benn, 1966; Introduction xviii.)

In the Induction to the sequel, Every Man out of His Humour (1600), Jonson poeticised the disordering effects on the psyche of the fluid properties of the four humours:

So in every human body

The choler, melancholy, phlegm, and blood,

By reason that they flow continually

In some one part, and are not continent,

Receive the name of Humours. Now thus far

It may apply itself unto the general disposition:

As when some one peculiar quality

Doth so possess a man, that it doth draw

All his affects, his spirits, and his powers,

In their confluctions, all to run one way,

This may be truly said to be a humour.

This notion of psychological excess, sometimes to the point of obsession, is applicable to most of the characters in Twelfth Night.

D. A Problem Play?

Twelfth Night is hardly a “problem play,” but issues of cruelty and violence surface towards the end and invite discussion:

- How will an audience respond to the gulling and imprisonment of Malvolio? Is this comedy or torture?

- How will an audience respond to Antonio’s arrest and threatened execution? See Dobson’s comment on the hidden violence of Illyria, Study Exercise Two, above.

- How will an audience respond to Orsino’s threat to kill Cesario-Viola as Olivia’s successful lover; and his/her consent to death: “And I, most jocund, apt and willingly/ To do you rest, a thousand deaths would die.” (Act 5, Scene 1, lines 120-31).

Bloom comments: “Orsino, not previously high in the audience’s esteem, is a criminal madman if he means this, and Viola is a masochistic ninny if she is serious….Wild with laughter, Twelfth Night is nevertheless almost always on the edge of violence” (234);

STRUCTURE OF TWELFTH NIGHT

The play’s action consists of changes and reversals that discourage analysis and demand that the audience fly with the unexpected. In the lunatic, lyrical world of Illyria, citizens and visitors alike are driven by the festive spirit, disorderly loves and hates, and zany eccentricities. The unlikely plot is part of the play’s appeal: the complicated events go against all the odds, fulfilling at all costs the audience’s wish for a happy ending. The comic resolution of Twelfth Night reminds us to have faith in good fortune and life’s possibilities.

There are some signs of the third-act climax typical of Shakespeare’s plays. However, action really consists simply of accelerating confusions and comic contretemps that build to a climax halfway through Act 5, when they are quickly resolved.

ACT 1:

Introduces most of the main and subplot characters; places Viola, disguised as Cesario, in Orsino’s court, and culminates when Olivia falls in love with Cesario.

ACT 2:

Introduces Antonio and Sebastian to the main plot and Fabian to the sub-plot; the action advances love confusions in the main plot and the gullings of Malvolio and Sir Andrew in the subplot.

ACT 3:

Momentum builds as gullings and confusions come to a climax: Malvolio’s cross-gartered yellow stockings and odd behaviour convince Olivia that he is mad; Sir Andrew and Cesario/Viola are on the point of a comic duel, when Antonio intervenes in defence of his friend, “Sebastian.” The Act ends with Antonio’s arrest; Sir Andrew sets out to look for and beat the “treacherous” Cesario.

ACT 4:

Instead, he comes upon Sebastian who belabours him with his own dagger hilt (confusion further confounded!). Sir Toby and Sebastian draw their swords, but Olivia berates her kinsman and dotes on the supposed Cesario; Feste (Sir Topas the curate) exorcises the fiend possessing the imprisoned Malvolio. Courted by Olivia, Sebastian meanwhile decides that he must be dreaming, or that he must be mad, or that Olivia is. The Act nevertheless ends with Sebastian and Olivia’s wedding.

Act 5:

Orsino and his company visit Olivia; the two noble households and all the sub-plot and main plot characters come together. Confusion builds yet further when Antonio, under arrest, accuses Cesario of treachery; when Olivia proves by the priest’s testimony that Cesario has married her; and when the battered Sir Andrew and Sir Toby accuse Cesario of beating them. Sebastian’s entrance stuns the company and begins the unravelling. Reconciliation reigns: brother and sister recognise each other in mutual love; Orsino rewards Cesario’s love by promising to marry him/her; Olivia claims Viola as a sister. Malvolio’s angry entrance exposing the plot against him, temporarily upsets the general rejoicing.

MAJOR CHARACTERS

When the wretched Malvolio is confined in the dark room for the insane, he ought to be joined there by Orsino, Olivia, Sir Toby Belch, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, Maria, Sebastian, Antonio, and even Viola, for the whole ninefold are at least borderline insane in their behaviour. (Bloom 226)

The comparatively featureless structure of Twelfth Night arises from the fact that the characters are driven by impulse and external events rather than by reasoning or long-term goals; they are lively, and embroiled in life.

Orsino

Orsino’s amiable erotic lunacy establishes the tone of Twelfth Night. (Bloom 230)

Orsino, far more in love with language, music, love and himself than he is with Olivia, or will be with Viola, tells himself (and us) that love is too hungry ever to be satisfied with any person whatsoever. (Bloom 229-230)

Critics have repeated the view fifty times that Orsino is more in love with love than with Olivia (J.M. Lothian and T.W. Craik, eds. Twelfth Night. Arden Shakespeare. London, Methuen, 1975: lii). A troubling egoism in fact powers Orsino’s love for Olivia, for example in his fantasy of rule and exclusive possession:

How will she love, when the rich golden shaft

Hath killed the flock of all affections else

That live in her; when liver, brain and heart,

These sovereign thrones, are all supplied and filled—

Her sweet perfections—with one self king!

(Act 1, Scene 1, lines 36-40)

This and other speeches of Orsino’s embody Shakespeare’s disillusioned understanding of sexual passion from the male perspective.

STUDY EXERCISE THREE: ORSINO

Orsino: There is no woman’s sides

Can bide the beating of so strong a passion

As love doth give my heart; no woman’s heart

So big to hold so much, they lack retention.

Alas, their love may be called appetite,

No motion of the liver, but the palate,

That suffer surfeit, cloyment, and revolt.

But mine is all as hungry as the sea,

And can digest as much. Make no compare

Between that love a woman can bear me

And that I owe Olivia. (Act 2, Scene 4, lines 94-104)

Bloom: “Here Orsino touches the sublime of male fatuity.” Comment.

Analyse the metre of this passage: how often does the stress fall on such words as “woman,” “my,” “mine,” “me,” and “I.” What effect does this metrical pattern have on Orsino’s characterisation at this point?

How do metaphors of feeding and the sea reinforce the contrast that Orsino makes between his and woman’s love?

Commentators on Twelfth Night have theorised what Bloom calls Orsino’s “amiable erotic lunacy” in other ways.

One of Orsino’s characteristics is extreme inconstancy of mind. In the opening scene he at first craves the music; quickly rejects it; and finally wanders off to indulge unhappy thoughts in a “canopy of flowers.” Later the down-to-earth Feste applies metaphors of fabric, gemstone, and voyaging to Orsino’s changeableness:

Now the melancholy god protect thee, and the tailor make thy doublet of changeable taffeta, for thy mind is a very opal. I would have men of such constancy put to sea, that their business might be everything, and their intent everywhere; for that’s it that makes a good voyage of nothing. Farewell. (Act 2, Scene 4, lines 72-77)

This analysis sums up the aimlessness of Orsino’s “fancy.” It can be further defined in relation to the theory of humours, which we have seen is probably one of Shakespeare’s comic targets in Twelfth Night. Dover Wilson in fact diagnoses Orsino’s changeableness as matching the symptoms of lover’s melancholy, as described in Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (Shakespeare’s Happy Comedies. London: Faber, 1962: 170).

Yet another way of understanding Orsino’s subjection to the “high fantastical” is in terms of a mask. According to Joseph H. Summers, Orsino is like other characters in Twelfth Night in that he has comically mistaken a mask that he has voluntarily put on as his true self: he has accepted the aristocratic and literary ideal of courtly or romantic lover as reality. (“The Masks of Twelfth Night,” in Twentieth Century Interpretations of Twelfth Night, ed. Walter N. King, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1968: 16).

On the other hand, these insights into the purely comical or satiric Orsino should not be taken too far. After all, Twelfth Night is appealing largely because it affirms the joy of erotic love. The characterisation of Orsino must therefore combine love’s silliness with love’s reality; somehow he must be maintained as a worthy love object for Viola. Shakespeare achieves this in part by having other characters testify to Orsino’s worthiness: the sea Captain describes him to Viola as “A noble duke, in nature as in name” (Act 1, Scene 2, line 25); and Olivia endorses this assessment:

I suppose him virtuous, know him noble,

Of great estate, of fresh and stainless youth,

In voices well divulged, free, learned, and valiant,

And in dimension and the shape of nature

A gracious person. (Act 1, Scene 5, lines 247-251)

However, Orsino is mainly humanised for the audience, beyond his lover’s lunacy, humour, melancholy or mask, through his affectionate conversations with the “youth” Cesario.

Viola

The “high fantastical” Orsino perhaps attracts [Viola] as an opposite; his hyperboles complement her reticences. (Bloom 232)

In contrast with Orsino’s extravagance in love, Viola’s is the true voice of feeling in Twelfth Night. She is a gauge for measuring the humours, lunacies and masks of the other characters. Although Viola alone wears a physical “mask”—her disguise as Cesario—for most of the play, her love for Orsino is openly revealed and real to the audience.

STUDY EXERCISE FOUR: VIOLA

Reread Act 2, Scene 4, paying special attention to Viola’s story of her “sister” (lines 104-120), told in response to Orsino’s assertion of male superiority in love (Exercise Four, above).

Who wins this “battle of the sexes”?

What is the effect of Viola’s story on the tone and pace of the comedy at this point?

Explain the force of Viola’s response to the music earlier in this scene, as an authentic evocation of love.

How is an audience likely to feel about Viola?

How does dramatic irony function throughout this scene? How does Viola’s story of her “sister” complicate the irony?

What form does the theme of “mutability”—the transience of youth and beauty—take in this scene? How important is this theme in Twelfth Night as a whole?

Bloom stresses that Viola adopts her male disguise from necessity, as “a way of going underground,” and not, like Rosalind, as an act of liberation. Like all other characters in Twelfth Night, Viola is subject to changing circumstances. She is sensible about the limits of her control over events, and surrenders to outcomes. For example, after deciding to serve in disguise at Orsino’s court, she says: “What else may hap to time I will commit” (Act 1, Scene 4, line 61); and extends this when she realises that Olivia has fallen in love with her persona as Cesario: “O time, thou must untangle this, not I!/ It is too hard a knot for me to untie” (Act 2, Scene 2, lines 41-42).

Viola wins the audience’s favour from her first landing on the coast of Illyria, when, despite heartbreak, she maintains a rational hope that her brother Sebastian has survived the shipwreck. This later gives the audience a measure for judging Olivia’s prolonged mourning-plan for her brother.

It is especially Viola’s loyalty in love that wins the audience’s favour: the poignancy of her seeking to win Olivia for the man she loves herself.

Although Viola adopts her male disguise defensively, she does so decisively, in a way that demonstrates both activity and an active imagination. If her dialogues with Orsino are somewhat sad, those with Olivia, Malvolio and Feste are combative and quick-witted. In trying to avoid her hilarious “sword fight” with the even more reluctant Sir Andrew, Viola invents an impressive list of excuses (Act 3, Scene4, lines 214-301).

In all, Bloom’s emphasis on Viola’s passivity may be excessive. As a counter-argument, you might like to consider the applicability to Viola of an earlier evaluation of Shakespeare’s women, by H. B. Charlton:

Shakespeare’s enthronement of woman as queen of comedy is no mere accident, and no mere gesture of conventional gallantry. Because they are women, these heroines have attributes of personality fitting them more certainly then men to shape the world towards happiness….These heroes [Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello], in effect, are out of equipoise: they lack the balance of a durable spiritual organism. It was in women that Shakespeare found this equipoise, this balance which makes personality in action a sort of ordered interplay of the major components of human nature. In his women, hand and heart and brain are fused in a vital and practical union, each contributing to the other. (Shakespearean Comedy. London: Methuen, 1938: Chapter IX)

Olivia

Equipoise, and the promotion of harmony in the self and in the world around her are not, however, obvious features of Olivia. Olivia’s foolish “humour” or “lunacy” in wasting so many youthful years in mourning is revealed in dialogue with Feste:

Feste: ….Good Madonna, give me leave to prove you a fool.

Olivia: Can you do it?

Feste: Dexteriously, good Madonna.

Olivia: Make your proof.

Feste: I must catechize you for it, Madonna. Good my mouse of virtue, answer me.

Olivia: Well, sir, for want of other idleness, I’ll bide your proof.

Feste: Good Madonna, why mourn’st thou?

Olivia: Good fool, for my brother’s death.

Feste: I think his soul is in hell, Madonna.

Olivia: I know his soul is in heaven, fool.

Feste: The more fool, Madonna, to mourn for your brother’s soul, being in heaven. Take away the fool, gentlemen.

(Act1, Scene 5, lines 52-68)

Viola treats Olivia’s idealistic mourning with similar realism, by literally removing her “mask”—her mourning veil—to reveal her beauty: “Lady, you are the cruellest she alive,/If you will lead these graces to the grave,/And leave the world no copy.” (Act 1, Scene 5, lines 230-232).

The realism of Feste and Viola rescues Olivia from her mourning “madness,” only to see it instantly replaced with the lunacy of her love for Cesario: “Even so quickly may one catch the plague?” Olivia asks (Act 1, Scene 5, line 284), deploying yet another metaphor for a distorting humour—sickness—that is common both in Twelfth Night, and generally in Elizabethan love poetry.

Although Olivia doesn’t arouse the love that an audience will feel for Viola, she is touching in her passion, which betrays her pride. Read the exchange between Viola and Olivia, Act 3, Scene 1, lines 81-161—a wonderful scene of dramatic irony and comic cross- purposes, where each character is equally appealing to an audience.

Malvolio

Quotes from Harold Bloom have helped to anchor our consideration of Twelfth Night throughout, and will assist us again in interpreting Malvolio. Bloom writes:

That accurate portrait of an affected time server is one of the most savage in Shakespeare. What happens to Malvolio is, however, so harshly out of proportion to his merits, such as they are, that the ordeal of humiliation has to be regarded as one of the prime Shakespearean enigmas. (239)

Malvolio obviously does not possess the infinitude of Falstaff or Hamlet, but he runs away from Shakespeare, and has a terrible poignance even though he is wickedly funny and is a sublime satire upon the moralising Ben Jonson. (Bloom 227)

Malvolio is, with Feste, Shakespeare’s great creation in Twelfth Night; it has become Malvolio’s play, rather like Shylock’s gradual usurpation of The Merchant of Venice….His dream of socio-erotic greatness—‘To be Count Malvolio!’—is one of Shakespeare’s supreme inventions, permanently disturbing us as a study in self-deception, and in the spirit’s sickness. (Bloom 238)

Let’s deal first with Malvolio’s characterisation, and secondly with his ordeal.

Malvolio’s name means “ill-will” and this may point to Shakespeare’s original intention in creating him. Malvolio does have ill-will towards Feste and Sir Toby Belch, both of whom he would like to see thrown out of Olivia’s household. Olivia uses another sickness metaphor in astutely defining Malvolio’s humour:

O you are sick of self-love, Malvolio, and taste with a distempered appetite. To be generous, guiltless, and of free disposition, is to take those things for bird-bolts that you deem cannon bullets. (Act 1, Scene 5, lines 85-87)

As this assessment implies, Malvolio is a comic study of introverted egoism. As such, he may be more relevant to some of us than we care to admit! Olivia diagnoses Malvolio as suffering from an all-consuming self-involvement (self-love) that rules out generosity, forgiveness, and a sense of proportion in relating to other people. Much of Malvolio’s behaviour confirms this diagnosis.

While he is no doubt efficient in carrying out his duties as a steward, Malvolio’s sense of superior worth isolates him emotionally and rules out fun and relaxation. Malvolio’s pride separates him from his instincts, the source of his energy. He condescends to Feste, hinting to Olivia that Feste is an inferior jester (Act 1, Scene 5, lines 78-84). He condescends to Cesario in delivering Olivia’s message and ring (Act 2, Scene 2, lines 5-16). He is officious in the strict sense of “identified with his office” when he quells the early morning revelries of Sir Toby, Sir Andrew and Feste—he carries out his office without humour, humanity or tact. He is, moreover, sanctimonious—he combines officiousness with a sense of moral superiority. Sir Toby sums up the steward’s entrenched pride in a famous accusation: “Dost thou think, because thou are virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?” (Act 2, Scene 3, lines 110-112). Malvolio is safe, however, until he makes the mistake of reporting Maria to Olivia (Act 2, Scene 3, lines117-120).

Malvolio is vulnerable to Maria’s scheme only because it builds on his conviction about his own worthiness, which it may be dangerous for any human to hold without qualification. (See Maria’s analysis of his false puritanism, Act 2, Scene 3, Lines 134-146.) Malvolio’s self-love, combined with ambition and a desire for revenge against Sir Toby, leads him to accept that Olivia is smitten and intends to marry him. In the famous “Box Tree Scene” (Act 2, Scene 5), Malvolio’s “sickness” comes to full comic expression, as he fantasises about how, as Olivia’s husband, he will lord it over Sir Toby, Sir Andrew and the servants. The commentary from the hidden watchers emphasises the diseased state of Malvolio’s imagination. This places him at the opposite pole from such down-to-earth but poetic figures as Viola and Feste: Maria:… this letter will make a contemplative idiot of him (lines 18-19); Sir Toby: Contemplation makes a rare turkey-cock of him; how he jets under his advanced plumes! (lines 30-31); Fabian: Look how imagination blows him.

It is this pretentiousness and humourlessness that makes Malvolio’s conduct in Olivia’s presence so funny (Act 3, Scene 4).

As far as Malvolio’s ordeal is concerned, I have a few thoughts to offer:

- The Elizabethans, and indeed Europeans into the eighteenth century, saw insanity as funny, rather than pitiable. Visiting Bethlehem Hospital (Bedlam) to laugh at the inmates’ antics, and to exchange jokes or insults was a favourite pastime. The theory of humours, and indeed the play’s treatment of the lunatic emotional excess that afflicts most of the characters, supports the relevance to Twelfth Night of what seems to us an unacceptable perspective. It was a common Elizabethan view also that moral failure caused insanity, and this seems to apply to Malvolio. In interpreting Twelfth Night, and especially the exorcism scene (Act 4, Scene 2), it is therefore important to decide if the context is Shakespeare’s time or our own.

- Although it’s fashionable in criticism of Twelfth Night to compare Malvolio with Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, Malvolio is by no means so eloquent a pleader for the audience’s understanding. When Malvolio returns in Act 5, following the comedy’s resolution, he is full of a self-justifying anger that discourages sympathy.

In 1602, however, after mentioning Twelfth Night’s Latin, Italian and Shakespearean genesis, John Manningham’s diary focussed on Malvolio’s gulling and imprisonment as the most memorable aspects of the performance he had seen. He refers to the gulling as “a good practise”—apparently to him a source of simple pleasure. The exorcism scene demands virtuoso acting from Feste, disguised as the curate Sir Topas, while Malvolio may be wholly or partly out of sight, hidden in “hideous darkness”—the so-called hell where he is said to be subject to possession by Satan. Perhaps there is poetic justice in this, given Malvolio’s pride? Perhaps Feste is the main focus of the scene that Shakespeare wrote?

STUDY EXERCISE FIVE: MALVOLIO

Many famous and well-loved actors, including Richard Briers and Nigel Hawthorne, have played Malvolio. For a list of recent productions, go to: http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Theater/sip/character/tn_malvolio/

Modern interpretations usually show little awareness of Malvolio’s pretentiousness, and instead emphasise his loyalty to his office, his humanity and pathos. Watch at least one modern DVD or video of Twelfth Night, with a view to arriving at your own evaluation of Malvolio. Does he deserve the fate that befalls him? What is your response to Maria and the other plotters? (See some judgments following.)

Maria, Sir Toby, Sir Andrew

If we’re naïve about Shakespeare, we feel we have to like these jokers, as embodying the spirit of twelfth night—not to like them, we fear, will align us with the humourless Malvolio and with the upper classes against the lower classes; with the powerful against the powerless.

The revellers and practical jokers—Maria, Sir Toby Belch, Sir Andrew Aguecheek—are the least sympathetic players in Twelfth Night, since their gulling of Malvolio passes into the domain of sadism….Both Belch and Aguecheek are caricatures, yet Maria, a natural comic, has a dangerous inwardness, and is the one truly malicious character in Twelfth Night. (Bloom 237-238)

Feste

We have seen that Feste is the main vehicle for Twelfth Night’s themes of mutability and carpe diem. These dominate his three solo songs, “O mistress mine!” (Act 2, Scene 3, lines 37-50); “Come away, come away, death” (Act 2, Scene 4, lines 50-65); and “When that I was a little tiny boy” (the play’s epilogue: Act 5, Scene 1, lines 385-405).

In discussing Olivia, we saw that Feste has the function of bringing her elaborate mourning down to earth. “Come away, come away death” similarly parodies the extremities of Orsino’s love lunacy. Feste is in fact the wise fool, “a witty fool,” who reveals the realities that underlie both the delusions and the aspirations of other central characters.

Feste’s wisdom includes a grounding in morality: his babble to Olivia recognises virtues and sins as part of the human condition (Act 1, Scene 5, lines 38-48). He is therefore comically appropriate as the curate who exorcises Malvolio’s devil. Feste’s own reality is his dread of dismissal by Olivia, a precariousness certain to earn him the audience’s sympathy.

As well as reminding players and audience of the realities of change and death (thanatos), Feste speaks for the reality of eros, the sexual drives that underlie and determine the emotional idealism of such characters as Olivia, Orsino, Viola and Sebastian. Sexuality is an important association of his name, which embodies the rejoicing and freedom from inhibitions associated with twelfth night festivities. His bauble (jester’s stick with an ass-eared head carved on it), which he addresses as Quinapalus, stands among other things for a penis, and his language bulges with sexual puns, e.g. “He that is well hanged in this world need fear no colours.”; “Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage,” etc., etc., etc!

When Shakespeare created Feste’s part in Twelfth Night, he must have had a virtuoso actor and singer at his disposal. Granville Barker comments:

Who was Shakespeare’s clown, a sweet-voiced singer and something much more than a comic actor? He wrote Feste for him, and later the Fool in Lear. At least, I can conceive of no dramatist risking the writing of such parts unless he knew he had a man to play them. (92)

Later commentators, such as Keir Elam, in what may be the definitive edition of Twelfth Night (London: Bloomsbury, 2008), assume that Robert Amin, an accomplished clown, mime, singer and himself a playwright, was Shakespeare’s original Feste.

Less Than Final Comment

Twelfth Night is not of Hamlet’s cosmological scope, but in its own very startling way it is another “poem unlimited.” One cannot get to the end of it, because even some of the most apparently incidental lines reverberate infinitely. (Bloom 227)

An Introduction to Colette’s The Cat

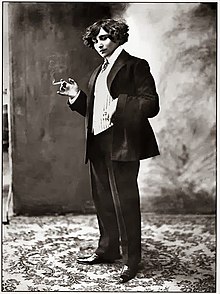

Page references in the following discussion are to Antonia White’s translation of The Cat in Colette. Gigi and The Cat. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1958. The Cat (La Chatte) was first published by Bernard Grasset, Paris, in 1933. This photo of Colette is by Henri Manuel:

Colette

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette (1873-1954) was a prodigiously productive writer of plays, novels, film scripts, reviews and short stories. English readers know her mostly for her novels, which have been available in translation for a long time, published by Penguin, and also made into films. She is, or was, as well known worldwide for her scandalous love life as for her writings.

Colette’s fiction falls into the three groups of her early Claudine novels, written before 1910 under the domination of her first husband, Willy; her mature works of the twenties and thirties, such as La Maison de Claudine (My Mother’s House), La Naissance du Jour (Break of Day) (1928), and La Chatte (1933); and works of the forties, in which she depicts her old age, such as L’Etoile Vesper (The Evening Star) (1946). Gigi, the second novel in your volume, was also first published in this period (1944).

The Cat

The introduction to the French edition of La Chatte locates it in a relatively tranquil period of Colette’s life, after she had survived her first marriage, and her love affair with Mathilde de Morne, named Missy, and was established in a relationship with Maurice Goudeket, 16 years her junior, whom she married in 1935, and to whom she remained attached until her death.

A writer on The Cat, Melanie Hawthorne, concludes her article, published in 1998, by noting that: “The ambiguity of La Chatte makes any definitive conclusion impossible, but in examining the political dimension of this novel, one might be forced to agree that “ce [n’]est [pas] si simple, c’est si difficile” (367). Hawthorne’s article nevertheless hints at a connection between Alain’s attitudes and Colette’s reputed, but not confirmed, sympathies with right-wing Nazi attitudes to class, gender and race in the period between the World Wars. Conversely, Hawthorne points to characteristics of Camille which “served to identify the modern woman who came to symbolize the loss of everything familiar in post-war [that is, after World War I] France” (363). This means that the reader’s sympathies are with Alain and against Camille. Hawthorne’s reading tends to revert to biographical responses to The Cat as a reflection of Colette’s well-known longing for the lost gardens of her Burgundian childhood, following her early first marriage and transportation to Paris. Under such interpretations, Alain’s empathy with Saha is similarly assumed to be a positive reflection of Colette’s even more famous love of cats. To quote Hawthorne for the last time, The Cat “is often viewed as a frivolous love story, as an illustration of Colette’s affinities with animals and nature” (361).

In this lecture I argue against this view of the novel. My argument is that language use and symbolism in The Cat undermines most of Alain’s attitudes, and validates Camille, both for being who she is and for her approach. I don’t claim much originality in arguing this view. The position is taken up by Marianna Forde, in an article published in The French Review in 1985, and she refers to other critics who arrived at similar conclusions about the novel.

I’m encouraged in my interpretation of The Cat by a reversal that occurs in the commentary by a conservative earlier critic, Margaret Davies. Davies’s opening summary of the plot reads: “Alain, the young man, runs away from the hard, shiny young girl, who as his wife is going to make a man of him, into the secure shadows of the heady garden of his childhood, seeking the ethereal, mobile presence of the cat which surges out of darkness like a spirit, accomplishing miracles of grace and movement, as beautiful as a demon” (86). However, at the end of her discussion, Davies writes:

It is, in fact, Alain who is the monster, having definitively chosen the ideal instead of the human, the Lost Paradise of the past instead of the vital force of the present. Life, life itself is the goal, even poetry can be withdrawal, abnegation. Colette had always known her own temptations and had always been able to write them out of her system” (89).

Narrative Viewpoint

Theorising about The Cat by Mieke Bal, referred to by Hawthorne, summarises the narrative position: “[The Cat is] told in the third person from the point of view of a character [Alain]” (362). In the process of “focalisation,” or more simply, focus on the internal life of one character, “the focalizer [or narrator] assumes the character’s view but without thereby yielding the focalizing to him” (362; my italics). In other words, the narrator remains outside of and detached from Alain, and invites us as readers to do the same. I would suggest that the focus on Alain should not be seen to imply that his attitudes are desirable; they do not invite the reader to sympathise with him uncritically. On the contrary, I suggest that the details that we discover about Alain’s inner and outer life are a warning on what to avoid. Alain exemplifies the crippling effects, bordering at times on absurdity and comedy, of self-absorption and the failure to mature. This is an awareness which The Cat conveys subtly to readers over the course of the narration, through an accumulation of narrative and descriptive details. The reader’s final realisation of Alain’s self-imposed narrowness seems to me to be all the more powerful, because of the initial impulse to identify and sympathise with him, engendered by the narrative perspective.

An interesting feminist paper could be written about the “male gaze” in relation to The Cat. You will have noticed in reading that one of the principal aspects of Camille which Alain dislikes and fears, because they penetrate his solitude, is her large eyes: “Catching sight again in the looking glass of the vindictive image and handsome dark eyes which were watching him” (67). Eyes pervade Alain’s delicious, self-chosen dreams—they belong to monstrous faces and people (71-73). Notice too Alain’s reaction to Camille’s photo, especially “her eyes enormous between two palisades of eyelashes” (74). This is a typical introvert’s dislike of being looked at, stemming I think from an only child’s experience of the parental gaze. Aldous Huxley refers to this in one of his early novels. Perhaps Alain identifies so closely with Saha because her eyes are impenetrable, invulnerable to the gaze of others. “Those deep-set eyes were proud and suspicious, completely masters of themselves” (68).

Under a feminist reading, a leading irony of The Cat is the fact that while Alain so much dislikes being looked at, he himself gazes constantly at Camille, and sits in judgment on her. It is this perspective that we as readers share for almost the whole length of the novel. As Forde points out, Alain is typically placed in static positions, viewing platforms from which he constantly looks at Camille, who is almost always presented as a being in motion. Alain therefore perpetrates on Camille the same intrusion by gaze, the same penetration, which he so strongly resists Camille imposing on him.

It is only in the final paragraph that this perspective is reversed, and we are allowed for the first time to look at Alain through Camille’s eyes, which he has considered throughout the novel to be so large and threatening. This reversal exposes a deep irony which has been hidden until now. The final insightful view, in which Alain at last becomes the observed, and not the observer, is highly significant. The cat, Saha, “was following Camille’s departure as intently as a human being”: Alain’s human gaze has been replaced by the impenetrable and invulnerable stare of the cat. Conversely Alain “was half-lying on his side, ignoring it. With one hand hollowed into a paw, he was playing deftly with the first green, prickly August chestnuts” (157). Alain has taken on the cat’s playful, self-sufficient and self-absorbed detachment. In the cat’s humanness and Alain’s likeness to a cat, it’s as if a final merging has occurred, confirming and hardening Alain’s egoistic stance, and even making it permanent. The green, prickly winter fruit of the chestnuts seems to symbolise both the end of this summer of opportunity—the marriage has lasted through the summer months, from May to August—and the coming of winter. The fruition suggested by the married state has not come to pass. However the unpromising winter harvest of the chestnuts may perhaps foretell a limited fruition in Alain’s future life.

Major Symbols

(i) Saha – The Cat

Both narratorially and symbolically, Saha accrues to Alain and is inimical or hostile to Camille. The union between young man and female cat has a sexual dimension. When Saha bites Alain, “He looked at the two little beads of blood on his palm with the irascibility of a man whose woman has bitten him at the height of her pleasure” (76). However, in truth, this is a pseudo-sexual rather than a sexual relationship; it’s a connection which evades the responsibilities that inevitably attend adult sexual relationships.

Later we read that “The admiration and understanding of cats was innate in him” (79). Camille is puzzled by Alain’s ability to understand what Saha is thinking and feeling (99). To her Alain’s relationship with and empathy with Saha is abnormal (139). It is clear that for Alain, Saha embodies something deep in himself, probably his “solitude, his egoism and his poetry,” to quote a list that occurs on p. 123. It’s significant later on that Alain’s mother refers to Saha as his “chimera” (151). A chimera is both a monstrous animal made up of the parts of other animals, and “a wild or unrealistic dream or notion.” For Alain, Saha is both monstrous and the embodiment of his unrealistic hope of remaining forever untroubled and insulated from life, like a child.

The manner in which the cat is discussed in relationship to Alain seems frequently to verge on the ridiculous, as if a subtle distortion in his viewpoint were being exposed. The way he addresses her: “My little bear with the big cheeks. Exquisite, exquisite, exquisite cat. My blue pigeon. Pearl-coloured demon” (70). (Demon is another interesting word, with connotations of the Greek daemon, or poetic inspiring spirit, and of course also devil.) “Ah! Saha. Our nights…” (71). Note the bathos, snobbery and egoism of the speech at the top of p. 80. It seems to me that this speech is an expose of Alain’s world view. Another ridiculous statement occurs after Alain has finally left the apartment and his marriage, when he is contemplating his restored connection at home with Saha: “He held her there, trusting and perishable, promised, perhaps, ten years of life. And he suffered at the thought of the briefness of so great a love” (145). Although the first sentence appears to invite the reader’s sympathetic approval, the second seems to go just a little too far, and wickedly to invite us to judge the situation from a more rational perspective—that of a narrator who does not cohere with the character’s viewpoint. The writing is a subtle exposé of deluded egoism.

A similar commentary can be applied to the language used about Camille after she has pushed the cat off the balcony: “A poor little murderess meekly tried to emerge from her banishment, stretched out her hand, and touched the cat’s head with humble hatred.” (132). “He lowered his head, imagining the attempted murder.” (140) “Thrown from the height of nine stories,” Alain thought as he watched her. “Grabbed or pushed. Perhaps she defended herself…perhaps she escaped to be caught again and thrown over. Assassinated.” (148-49) Perhaps we are on Alain’s side as he imagines Saha’s struggle for life. However, the last word, “Assassinated,” surely goes too far, and reminds us that after all it is a cat, and not a human being that is being referred to. Once again, our sympathy suddenly runs up against a sense of proportion, confronts reality.

(ii) Alain’s Home

(Much of this discussion is indebted to Marianna Forde’s article, “Spatial Structures in La Chatte” which I recommend to you. Forde discusses binary oppositions associated with Alain and Camille: down/up, closed/open, static/dynamic, past/future, old/modern, noble/common, living/dead.

1. Garden

The garden in suburban Paris at Neuilly is low down, five steps lower than the house branch. Forde considers in depth the significance of Alain’s association with the earth, with low places such as the garden and the house, the worn old servants, who are half-buried in their basement (105), and Camille’s contrary associations with height and open spaces. The garden is not usually presented in positive terms, but is associated, as in the first description (64) with blackness, or dark green, with fossilisation (calcined twigs), and old age. An iron fences walls it off from the real world (68). Far from being a place of fruition, the garden is presided over by a dead yew tree, which is mentioned no fewer than four times. Yew trees traditionally grow in cemeteries. Forde points out that a long hanging cluster of the poisonous laburnum hangs directly in front of Alain’s window (69). She suggests that the garden is in fact poisonous to Alain, because, like his attachment to Saha, it contributes to the stunting of his emotional growth. It protects him from the full gamut of adult experience. The prevalent colours of the garden are dark green and black. When colours other than these are associated with the garden, the effect is not so enchanting (145, bottom).

Other negative associations are with over-cultivation and over-civilisation, not in a good sense: “the secret exhalation of the filth which nourishes fleshy, expensive flowers” (90). There’s a sense of fossilisation, of the same summer scenes being acted and re-enacted again and again (92). The garden is also associated with age: “One of the oldest climbing roses carried its load of flowers, which faded as soon as they opened” (95). At his breakfast of “liberation” Alain receives “an ill-made, stunted little rose” (147).

2. Servants

There is a repetitive emphasis on the age of the servants, Emile the butler, and Juliette, the Old Basque woman with a beard. The physical descriptions of these are always negative, e.g., “The old butler muttered answers as shallow and colourless as himself” (94); “he raised his pale, oyster-coloured eyes, which had never laughed in their life, to the pure sky” (94).

3. Alain’s Room

The theme which merges most strongly in the depictions of Alain’s room, and himself in it, is his undeveloped childishness, his adolescence which is continuing into his twenties. The connections made between Alain and childhood, adolescence and childishness are innumerable in The Cat. When Alain reaches his room, he examines his face in the mirror, in a passage which demonstrates his self-obsession, if not narcissism (70). The box of ancient childish treasures, “bright and worthless as the coloured stones one finds in the nests of pilfering birds” (69), which he refuses to discard likewise suggests his refusal to let go of the past, a comment follows on his life as an only child (top of 70). At the end, when Alain returns to the setting of his pampered youth, his mother welcomes him by treating him again like a child (bottom of 149), and the old servants fall again into the patterns of a lifetime by serving “Monsieur Alain.” There is however restraint and a certain perceptiveness in his mother’s reaction, especially in her knowledge that a man has to be born many times with no other assistance than that of chance, of bruises, of mistakes (150-51). Like Alain, she nevertheless condescends to Camille as a member of the middle classes, classes that are only partially redeemed by their wealth (151).

Camille

It is important to distinguish between the information which the narrator reveals about Camille and Alain’s judgmental and resisting responses. That we as readers are invited to judge Alain for his judging of Camille seems plain from one of the early descriptions, in which it becomes clear that Alain prefers the shadow to the flesh-and-blood woman (65):

Unclasping her hands, the girl walked across the room, preceded by the ideal shadow… ‘What a pity!’ sighed Alain, Then he feebly reproached himself for his inclination to love in Camille herself some perfected or motionless image of Camille. This shadow, for example, or a portrait or the vivid memory she left him of certain moments, certain dresses” (65-66).

At this point, Alain is in a typically lowered, static state, watching Camille, who is dynamically moving about.

When Alain selects a photo of Camille for his bedroom, it is one “which bore no resemblance to Camille or to anyone at all” (74). The photo is of someone with accentuated features, “her painted mouth vitrified in inky black” (74). You should notice that this does not accurately describe the physical Camille. Camille’s make-up is not presented as hardening her or making her brittle. On the contrary, there is approval implied, both of her manner of self-presentation and of her body itself. Alain breathes in , “under a perfume too old for her, a good smell of bread and dark hair” (68). “Made-up with skill and restraint, her youth was not obvious at the first glance” (81). Cf. Also 95. “She was looking pretty every evening at that particular hour; wearing white pyjamas, her hair half loosened on her forehead and her cheeks very brown under the layers of powder she had been superimposing since the morning” (100). The vivid colours of life are captured (101) in the description of Camille laughing as she eats the melon. Alain detects, “how vivid a certain cannibal radiance could be in those glittering eyes and on the glittering teeth”; but this reaction opposes the other part of the description, and the reader is not obliged to agree. On the contrary, what the make-up does imply, is Camille’s wish to be attractive and pleasing to Alain. Cf. 85. In fact, her longing that he will love her spontaneously is obvious in almost every encounter, and in every encounter he hangs back.

Alain’s dislike of Camille’s natural and uninhibited sexuality, his repugnance at her parading around in the nude is undercut by the subtle revelations which are given, twice at least, that he has had mistresses in the past. The scene of the morning after their wedding night (83) is a none-too-subtle revelation of Alain’s judgmental snobbery: “She’s got a common back…She’s got a back like a charwoman.” Such comments are juxtaposed with Colette’s positive presentation of Camille’s physical grace: “But suddenly she stood upright again, took a couple of dancing steps and made a charming gesture of embracing the empty air.” Lightness and airiness typify descriptions of Camille. Alain’s sense that Camille is becoming fat while he becomes thinner by lovemaking is presented, significantly as the “age-old misogynist complaint.”

The Wedge

While Alain is at home on and below the ground at Neuilly, the airiness of the Wedge, a modern apartment on the ninth floor of a building called Quart-de-Brie is associated with Camille. The obvious triangular symbolism of the Wedge, with the tops of the three dying poplar trees visible outside (101), an indication perhaps of the ménage à trois formed by the two humans and the cat, is typical of the subtle symbolism operating throughout The Cat. The Wedge is open to breezes, which are never still (93). While Camille enjoys its openness to the elements, Alain tends to hole up there, especially in the little annex where he sleeps on the hard narrow bed, “the waiting room bench.” He brings in the pot plants to protect them from the wind.

The fireworks watched from the Wedge (135-37) may symbolise the brilliance and transience of Alain and Camille’s love. Despite the orgasmic connection, I think that the rockets are more closely connected with Camille’s unhappiness as she realises the hopelessness of her relationship: “It never lasts long enough,” she said plaintively (136). “No. It’s you. It’s you who… who don’t love me” (137). If we’re tempted to condemn Camille as the attempted murderer of the cat, it’s scenes and words of hers such as these that we should look at. In fact the near-homicide of the cat was the culminating act in Camille’s attempts to save her marriage, attempts that typify all her interactions with Alain from the very beginning. It’s a big and energetic act, which contrasts strongly with Alain’s predictable horror and condemnation. Consider the ridiculous over-statement on 155, “A little blameless creature etc….”

After she arrives at the Wedge, Saha follows Alain in avoiding the winds, though, like Camille, she passes her time watching from the balcony and shows no fear of heights. The culmination of Alain’s reaction against the Wedge comes in his fear of the storm. He seeks Camille’s protection, but characteristically withdraws when the storm is over. Few of us indeed get through life without facing storms, a truth that it would profit Alain to keep in mind.

Discussion Topics

1.Discuss the possible significance of eyes, dreams, gardens, the number three. Any other symbols?

2.Which does Saha most resemble – Camille or Alain? Or is it that they resemble her? (Which is primary?)

3.Discuss Saha as “character” and as symbol.

4.How do you feel about Camille’s attempted murder of Saha?

5.Discuss the representation and significance of subsidiary figures in The Cat, e.g. the parents, especially Alain’s mother; and the servants.

6. What feminist assumptions do you find in The Cat? Or, does the novel invite the reader’s sympathy for Alain? What, if anything, is unappealing about Camille?

7. Assuming that they are symbolic, what light do the roadster and the rockets cast on the contrasting characters of Camille and Alain?

8. Discuss ambiguity in The Cat.

9. Discuss The Cat as a despairing comment on heterosexual connection.

Colette’s The Cat: Selected Studies

Callander, Margaret M. Le Ble en herbe and La Chatte. Critical Guides to French texts. London; Valencia : Grant & Cutler; Artes Graficas Soler, 1992.

Davies, Margaret. Colette. Writers and Critics. Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd, 1961. [The Cat 85-89]

Dormann, Genevieve. Colette: A Passion for Life. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984. [Colette in pictures!]

Forde, Marianna. “Spatial Structures in La Chatte.” The French Review: Journal of the American Association of Teachers of French, Champaign, IL (FR). 58:3 (1985): 360‑367.

Hawthorne, Melanie. “’C’est si simple… C’est si difficile’: The Ideological Ambiguity of Colette’s La Chatte.” Australian Journal of French Studies (AJFS). 35:3 (1998): 360‑68.

Ladimer, Bethany. “Moving Beyond Sido’s Garden: Ambiguity in Three Novels by Colette.” Romance Quarterly, Washington, DC (KRQ) 36:2 (1989): 153‑167.

George Herbert: Poet and Spiritual Guide

George Herbert (1593-1633) belonged to the school of seventeenth-century which included John Donne, Henry Vaughan, Richard Crashaw, Abraham Cowley and Thomas Traherne. Helen Gardner’s introduction to her edition, The Metaphysical Poets (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966), is an expert discussion of the leading features of this school. Present-day Bemerton residents have provided an excellent illustrated biography of Herbert: http://www.georgeherbert.org.uk/about/ghb_group.html. I highly recommend also Amy M. Charles, A Life of George Herbert (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press,1977). Guides to some of Herbert’s best-known and best-loved poems follow. (more…)

Jennifer Rogers: Jigsaws

Jigsaws was first performed at the Hole in the Wall theatre in Perth in 1988. It was published by Currency Press in the same year. A season at La Boite Theatre, Brisbane, followed in January-February 1990. See the plot outline and photo of performers at <archive.laboite.com.au/1990/jigsaws> . Jigsaws was revived at the Koorliny Arts Centre, Kwinana, WA, February 12 – 27, 2013. All the characters are women–a rarity in the traditional theatre and a feminist statement in itself.

George Johnston’s My Brother Jack

These three lectures trace themes of war, soldiership, masculinity, femininity, and family relationships as they unfold sequentially through My Brother Jack.

LECTURE ONE: BOYHOOD

My Brother Jack was first published to critical acclaim in 1964. It follows the lives of David Meredith and his brother Jack from David’s childhood in 1914 (when he was three) to 20th March 1945, when British forces recaptured Mandalay, Central Burma, from the Japanese army. The lives of the two leading characters are deeply affected by the two world wars and by the world-wide Depression of the early 1930s. Johnston also explores ways in which these events affected Australia more generally. More particularly, his novel documents changes in family and suburban life over the thirty-year period. My Brother Jack considers complex issues of male self-definition, of ethics and family relationships.

The following are among the questions raised:

- War is a disaster, but does it possess the positive aspect of providing essential self-definition and a cause for men like Jack?

- Is Jack presented unequivocally as an ideal Australian man?

- What are the qualities of the ideal Australian man?

- If Jack embodies this ideal, where does that leave David?

- How justified is David’s sense of himself as weak and selfish and of Jack as strong, outgoing and affectionate?

- Does the fact that he has a sensitive conscience exonerate David?

- How justified is David’s guilt about his own social and material success in relation to Jack’s failure in these spheres?

- How do you define a man’s failure or success?

- What gender issues are raised by this novel?

- How does the ideal of a man as a brave fighter fare in My Brother Jack?

- “In My Brother Jack individual morality is the primary interest, overriding themes of heroism, war, definitions of manhood, and representations of the Australian national character.” How far do you agree?

The Young David Meredith

The character of David Meredith is a key for interpreting My Brother Jack. We’ll begin our exploration therefore by mustering and exploring clues about David’s character. Since Jack is the main reference point for David’s characterisation, we’ll also be discussing him.

Two further questions concern David as narrator:

- How reliable is he, especially as a judge of merit and character?

- Is the reader able to read between the lines of what David reveals and arrive at judgments of himself and Jack that differ from David’s own?

Childhood

David’s childhood seems to have been neglected and lonely. When his father returns from overseas service in World War I, he describes himself as being charged with “a huge numbing terror”, and as “sobbing with fear” (p. 4). He reacts to the welcome home party by vomiting (p. 5). This symbolises his response to the War as it has affected his family. He lives in a house crammed with maimed men, and the thought of dying or being wounded in war fills him with terror. He reacts similarly to hospital visits to the war wounded—with “desperate Sunday feelings…an extension of the terror that I knew to be real” (p. 9). The War’s permanent effects on him are summed up early:

Yet what is significant is to realize how every corner of that little suburban house must have been impregnated for years with the very essence of some gigantic and sombre existence that had taken place thousands of miles away, and quite outside the state of my being, yet which ultimately had come to invade my mind and stay there, growing all the time, forming into a shape. (p. 11)

Already in his early childhood David is judging himself as inferior to Jack: “it is perfectly true that the period which had turned him into a wild one had made me something of a namby-pamby” (10). The incident with the Dollicus creeper seeds (pp. 10-11) is significant because it reveals that one person in the family loved David—his grandmother Emma—but he seems to have been starved for affection from others. Together with the family’s favourite Christian name, Jack as the elder son inherited the family’s approval.

Suburban Life: First Round

Another trait of David’s that emerges from the early chapters of My Brother Jack is dislike and contempt for the “undistinguished,” “mundane” suburban house in which he grew up. He plays on the irony of the house’s name, Avalon, the mythical fairy kingdom featured in romances of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. He pours scorn also on attempts by nearby owners to dress up their small houses with fancy names (p. 29). Are there good reasons for David’s hatred of suburbia, do you think, or is he just a snob? The following passage, opening Chapter 3, is relevant:

This world, without boundaries or specific definition or safety, spread forever, flat and diffuse, monotonous yet inimical, pieced together in a dull geometry of dull houses behind silver-painted fences of wire or splintery palings or picket fences and hedges of privet and cypress and lantana… (p. 29)

What are features of suburbia, then, that David objects to? How far does the widespread disillusionment about World War I, and the great police strike of the 1920s, contribute to his attitude? He objects especially to the mediocrity of the suburbs, the fact that “they lacked the grim adventure of true poverty” experienced in the downright slums of Fitzroy and Collingwood (p. 35).

Early Contrasts with Jack

As a teenager, Jack responds to his situation by fighting, and this is the advice that he gives to David: “Listen, nipper, you got to have a go at it. Even if you know you can’t bloody win you still got to have a go” (p. 31). Jack takes on the leader of the gang who broke his sweetheart’s shop window. By contrast David responds to the life around him by curling up in the seaman’s chest in the Front Room. Jack develops a passion for cricket and football, and as a mere youth takes on the six-foot Snowy Bretherton in a boxing match, finally winning against him. Meanwhile David, with no aptitude for sport, beats up the weakly, epileptic Harry Meade, to Jack’s disgust. Jack’s final childhood triumph is when he warns his father not to repeat the Saturday night bathroom punishments (p. 47). David’s punishments continue, however, until his father is held back by the combined efforts of the doctor and David’s mother. Jack’s chivalry, towards his girlfriend, his mother and Harry, is felt by David to be an admirable trait that he himself lacks. We might ask however whether Jack’s chivalry might have extended to the protection of his younger brother?

More significantly, we are also entitled to ask: Is David a failure in his own eyes and in the eyes of others, because by nature he lacks the qualities that define young Australian manhood, as embodied in Jack? These qualities are as follows.

- Jack is a larrikin and a rebel;

- a non-nerd—David is more academic;

- a good fighter;

- a good protector of the weak;

- a good sportsman and interested in sport;

- possesses a sense of fair play.

But how justified is David in blaming himself for lacking these qualities? Might another culture or time have encouraged him to value the qualities that are naturally his, such as sensitivity and imagination? Might a different culture have allowed him space for self-acceptance and self-esteem?

Working Lives

As an unmarried youth, Jack displays qualities that David appears to admire unreservedly, but which may disquiet some present-day readers. Jack plays a gross practical joke on his plumber-employer, Mr. Foley, which costs him his apprenticeship. At seventeen he is sexually confident and determined to “score”—“he saw sex early and clearly” (p. 51); Johnston uses the simile of a tomcat (p. 54). Jack has a colourful turn in abusive phrases, and his attitude to women, to put it mildly, is disrespectful: “‘If the Old Man had to saw Jean Harlow in halves,’ he said bitterly, “he’d damn’ well see to it that I got the half that talks” (p. 51). He also collects trophies of sexual conquests that are demeaning to the women involved (p. 55). He nevertheless remains attractive because of his immense gusto for life. David as narrator conveys this vibrancy in eating metaphors:

Anything he tackled was tackled with immense gusto, almost as if he had to eat life in huge gulps…while his appetite was strong…or before they cleared away the table. (p. 51)

The prospect of ‘landing a sheila’ would fill him with the same kind of gluttonous rapture as a second or third helping of his favourite food, which continued to be Mother’s steamed jam roly-poly. (p. 52)

What is the sub-text of such metaphors? Do they imply a negative comment on Jack’s attitude, as reducing what might be a source of emotional and even spiritual fulfilment to its grossest physical level? Or is Jack’s attitude to sex and women to be expected and condoned as natural in an adolescent boy? After all, love and marriage later produce a major change in him.

A further point is that Jack at this early stage of his life is in revolt against “wowsers,” defined in his terms on page 53. He calls David a “wowser” because of his sexual bashfulness, stemming in part from his pimples and “skeletonic shape” (p. 53). The reader may want to ask if Jack’s put-downs of David, including his fear that David might be led into homosexuality, stem from sibling rivalry and an intuition that David wields a creative intelligence that is not one of his own gifts. David departs early from the model of young Australian manhood approved in the period by being a reader. He and his three friends persist in reading great books by international authors. David describes this as “groping and pretending” (p. 57). In other words, this group perseveres in exploring life’s possibilities in a rational if painful and limited way. From this David begins to intuit that writing is his vocation, but initially he sees his writing, which he conceals from Jack, as a sign that he lacks the natural confidence and enthusiasm that his brother displays: “I was setting out to try to side-step a world I didn’t have the courage to face” (p. 58). David also believes that using his imagination and giving time to writing established a pattern of fearful evasion that he was to follow “for years to come” (p. 58).

All of these contrasts contribute to David’s feeling that he is by nature inferior to his brother. He lacks Jack’s enthusiasm for living, because he sees more drawbacks. His personality does not match the values of the culture in which he grows up. However how much substance is there to justify his conviction that Jack is the better young man, and he himself is a moral failure?

David the Young Writer

When apprenticed as a lithographer at the Klebendorf factory, David’s feeling of being inferior is deepened by contrast with the conscientious, generous and talented Young Joe, who at work takes his brother’s place as a foil to David’s conscience. By skipping the afternoon and night art and painting classes needed for his lithography training, David betrays the trust of kindly, admirable, tactful people. However, in a moment that he calls “the enlightenment” (p. 73), he realises that he wants to write about the old sailing ship days. He sends his first article to the Morning Post, under the pen name of Stunsail. Chapter 5 ends: “I was fifteen. And I was a writer. Lonely and secretive, and desperately anonymous, but still a writer” (p. 75). David has brought into the light the secret power that had been hidden from him by his sense of inferiority to Jack. A question to be asked is: How forgivable are the betrayals that he has committed on his way to this goal?

David’s Dishonesties

These betrayals have mainly to do with David’s apprenticeship at Klebendorf’s lithography firm. He falsely claims as his own the work of a fellow apprentice, Young Joe. He skips classes; in one episode claims as his own work that Young Joe and his father have completed in three hours of hard overtime; he steals two good studies from Young Joe which ensure his graduation to the Life Class in painting; forges a painting of the Grafton for his grandmother’s birthday; and buys an old Remington typewriter with a £5 birthday present that his mother intended him to spend on paints. David’s energy becomes focused on his creative work at home rather than on his ineptitude at work. However, his sense becomes entrenched as a source of lifelong pain—read the paragraph beginning, “In childhood and adolescence…” (p. 83). How do you as a reader respond to a character who judges his own petty defections so savagely?

In Lectures Two and Three we’ll trace David’s and Jack’s development through the novel. We may be able to convince ourselves that David’s harsh judgement of himself and admiration for his brother are justified.

LECTURE TWO: MANHOOD

When David and Jack Meredith were growing up in suburban Melbourne during World War I, their parents’ absence overseas profoundly affected their boyhood and family life in suburban Melbourne. The brothers developed opposite responses to the war and to their father’s brutality. Jack adopted a heroic approach: “Even if you can’t bloody win you still got to have a go” (p. 31). He became a larrikin (teenage tearaway), often in fights, chasing girls for sex and playing pranks on his employer. He approached life with a consuming energy. By contrast, David’s imagination and sensitivity meant that he experienced mostly fear. His chosen vocations of writer and journalist allowed him to avoid close ties and involvement. He blames himself, in contrast with Jack, for dishonesties and petty theft, and emerges from childhood with an inferiority complex. He especially feels that he is morally inferior to his brother and to the kindly, honest staff who practice their craft and lead blameless lives at Klebendorf’s.

As David and Jack mature to adulthood and their differences deepen, the reader begins to agree with David’s evaluation of himself as morally inferior. A way to understand the contrast between the brothers is to think of Jack as representing the traditional heroic ideal of an Australian man–a fighter and a sportsman who is also at home in the bush. Jack is the sort of character admired in A. B. Paterson’s ballad, The Man from Snowy River. David on the other hand represents twentieth-century suburban man, a later figure in history. Written postwar, My Brother Jack can be further understood as the product of a society undergoing an ideological transition between the bush and the city. (Most Australians have always lived in towns and cities, so I’m talking about an internal, not a physical transition.) Manhood ideals did not keep up with this transition. Indeed, many Australians found it was difficult if not impossible to choose the mundane rather than the adventurous, to prefer the suburban over the soldierly, or to value brains more than courage and physical strength and skills. Jack embodies the old ideal, for which so much nostalgia was felt, while David represents the “new man” who is effective in business, a wielder of words rather than weapons, but morally indifferent or bankrupt. David wears a business suit, not bush gear; the romantic turned-up hat of the Australian soldier—bushmen volunteers—with its badge of the rising sun is not for him.

Before the Depression