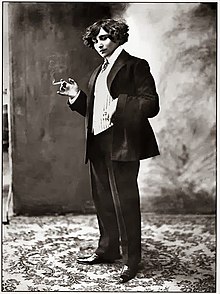

Page references in the following discussion are to Antonia White’s translation of The Cat in Colette. Gigi and The Cat. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1958. The Cat (La Chatte) was first published by Bernard Grasset, Paris, in 1933. This photo of Colette is by Henri Manuel:

Colette

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette (1873-1954) was a prodigiously productive writer of plays, novels, film scripts, reviews and short stories. English readers know her mostly for her novels, which have been available in translation for a long time, published by Penguin, and also made into films. She is, or was, as well known worldwide for her scandalous love life as for her writings.

Colette’s fiction falls into the three groups of her early Claudine novels, written before 1910 under the domination of her first husband, Willy; her mature works of the twenties and thirties, such as La Maison de Claudine (My Mother’s House), La Naissance du Jour (Break of Day) (1928), and La Chatte (1933); and works of the forties, in which she depicts her old age, such as L’Etoile Vesper (The Evening Star) (1946). Gigi, the second novel in your volume, was also first published in this period (1944).

The Cat

The introduction to the French edition of La Chatte locates it in a relatively tranquil period of Colette’s life, after she had survived her first marriage, and her love affair with Mathilde de Morne, named Missy, and was established in a relationship with Maurice Goudeket, 16 years her junior, whom she married in 1935, and to whom she remained attached until her death.

A writer on The Cat, Melanie Hawthorne, concludes her article, published in 1998, by noting that: “The ambiguity of La Chatte makes any definitive conclusion impossible, but in examining the political dimension of this novel, one might be forced to agree that “ce [n’]est [pas] si simple, c’est si difficile” (367). Hawthorne’s article nevertheless hints at a connection between Alain’s attitudes and Colette’s reputed, but not confirmed, sympathies with right-wing Nazi attitudes to class, gender and race in the period between the World Wars. Conversely, Hawthorne points to characteristics of Camille which “served to identify the modern woman who came to symbolize the loss of everything familiar in post-war [that is, after World War I] France” (363). This means that the reader’s sympathies are with Alain and against Camille. Hawthorne’s reading tends to revert to biographical responses to The Cat as a reflection of Colette’s well-known longing for the lost gardens of her Burgundian childhood, following her early first marriage and transportation to Paris. Under such interpretations, Alain’s empathy with Saha is similarly assumed to be a positive reflection of Colette’s even more famous love of cats. To quote Hawthorne for the last time, The Cat “is often viewed as a frivolous love story, as an illustration of Colette’s affinities with animals and nature” (361).

In this lecture I argue against this view of the novel. My argument is that language use and symbolism in The Cat undermines most of Alain’s attitudes, and validates Camille, both for being who she is and for her approach. I don’t claim much originality in arguing this view. The position is taken up by Marianna Forde, in an article published in The French Review in 1985, and she refers to other critics who arrived at similar conclusions about the novel.

I’m encouraged in my interpretation of The Cat by a reversal that occurs in the commentary by a conservative earlier critic, Margaret Davies. Davies’s opening summary of the plot reads: “Alain, the young man, runs away from the hard, shiny young girl, who as his wife is going to make a man of him, into the secure shadows of the heady garden of his childhood, seeking the ethereal, mobile presence of the cat which surges out of darkness like a spirit, accomplishing miracles of grace and movement, as beautiful as a demon” (86). However, at the end of her discussion, Davies writes:

It is, in fact, Alain who is the monster, having definitively chosen the ideal instead of the human, the Lost Paradise of the past instead of the vital force of the present. Life, life itself is the goal, even poetry can be withdrawal, abnegation. Colette had always known her own temptations and had always been able to write them out of her system” (89).

Narrative Viewpoint

Theorising about The Cat by Mieke Bal, referred to by Hawthorne, summarises the narrative position: “[The Cat is] told in the third person from the point of view of a character [Alain]” (362). In the process of “focalisation,” or more simply, focus on the internal life of one character, “the focalizer [or narrator] assumes the character’s view but without thereby yielding the focalizing to him” (362; my italics). In other words, the narrator remains outside of and detached from Alain, and invites us as readers to do the same. I would suggest that the focus on Alain should not be seen to imply that his attitudes are desirable; they do not invite the reader to sympathise with him uncritically. On the contrary, I suggest that the details that we discover about Alain’s inner and outer life are a warning on what to avoid. Alain exemplifies the crippling effects, bordering at times on absurdity and comedy, of self-absorption and the failure to mature. This is an awareness which The Cat conveys subtly to readers over the course of the narration, through an accumulation of narrative and descriptive details. The reader’s final realisation of Alain’s self-imposed narrowness seems to me to be all the more powerful, because of the initial impulse to identify and sympathise with him, engendered by the narrative perspective.

An interesting feminist paper could be written about the “male gaze” in relation to The Cat. You will have noticed in reading that one of the principal aspects of Camille which Alain dislikes and fears, because they penetrate his solitude, is her large eyes: “Catching sight again in the looking glass of the vindictive image and handsome dark eyes which were watching him” (67). Eyes pervade Alain’s delicious, self-chosen dreams—they belong to monstrous faces and people (71-73). Notice too Alain’s reaction to Camille’s photo, especially “her eyes enormous between two palisades of eyelashes” (74). This is a typical introvert’s dislike of being looked at, stemming I think from an only child’s experience of the parental gaze. Aldous Huxley refers to this in one of his early novels. Perhaps Alain identifies so closely with Saha because her eyes are impenetrable, invulnerable to the gaze of others. “Those deep-set eyes were proud and suspicious, completely masters of themselves” (68).

Under a feminist reading, a leading irony of The Cat is the fact that while Alain so much dislikes being looked at, he himself gazes constantly at Camille, and sits in judgment on her. It is this perspective that we as readers share for almost the whole length of the novel. As Forde points out, Alain is typically placed in static positions, viewing platforms from which he constantly looks at Camille, who is almost always presented as a being in motion. Alain therefore perpetrates on Camille the same intrusion by gaze, the same penetration, which he so strongly resists Camille imposing on him.

It is only in the final paragraph that this perspective is reversed, and we are allowed for the first time to look at Alain through Camille’s eyes, which he has considered throughout the novel to be so large and threatening. This reversal exposes a deep irony which has been hidden until now. The final insightful view, in which Alain at last becomes the observed, and not the observer, is highly significant. The cat, Saha, “was following Camille’s departure as intently as a human being”: Alain’s human gaze has been replaced by the impenetrable and invulnerable stare of the cat. Conversely Alain “was half-lying on his side, ignoring it. With one hand hollowed into a paw, he was playing deftly with the first green, prickly August chestnuts” (157). Alain has taken on the cat’s playful, self-sufficient and self-absorbed detachment. In the cat’s humanness and Alain’s likeness to a cat, it’s as if a final merging has occurred, confirming and hardening Alain’s egoistic stance, and even making it permanent. The green, prickly winter fruit of the chestnuts seems to symbolise both the end of this summer of opportunity—the marriage has lasted through the summer months, from May to August—and the coming of winter. The fruition suggested by the married state has not come to pass. However the unpromising winter harvest of the chestnuts may perhaps foretell a limited fruition in Alain’s future life.

Major Symbols

(i) Saha – The Cat

Both narratorially and symbolically, Saha accrues to Alain and is inimical or hostile to Camille. The union between young man and female cat has a sexual dimension. When Saha bites Alain, “He looked at the two little beads of blood on his palm with the irascibility of a man whose woman has bitten him at the height of her pleasure” (76). However, in truth, this is a pseudo-sexual rather than a sexual relationship; it’s a connection which evades the responsibilities that inevitably attend adult sexual relationships.

Later we read that “The admiration and understanding of cats was innate in him” (79). Camille is puzzled by Alain’s ability to understand what Saha is thinking and feeling (99). To her Alain’s relationship with and empathy with Saha is abnormal (139). It is clear that for Alain, Saha embodies something deep in himself, probably his “solitude, his egoism and his poetry,” to quote a list that occurs on p. 123. It’s significant later on that Alain’s mother refers to Saha as his “chimera” (151). A chimera is both a monstrous animal made up of the parts of other animals, and “a wild or unrealistic dream or notion.” For Alain, Saha is both monstrous and the embodiment of his unrealistic hope of remaining forever untroubled and insulated from life, like a child.

The manner in which the cat is discussed in relationship to Alain seems frequently to verge on the ridiculous, as if a subtle distortion in his viewpoint were being exposed. The way he addresses her: “My little bear with the big cheeks. Exquisite, exquisite, exquisite cat. My blue pigeon. Pearl-coloured demon” (70). (Demon is another interesting word, with connotations of the Greek daemon, or poetic inspiring spirit, and of course also devil.) “Ah! Saha. Our nights…” (71). Note the bathos, snobbery and egoism of the speech at the top of p. 80. It seems to me that this speech is an expose of Alain’s world view. Another ridiculous statement occurs after Alain has finally left the apartment and his marriage, when he is contemplating his restored connection at home with Saha: “He held her there, trusting and perishable, promised, perhaps, ten years of life. And he suffered at the thought of the briefness of so great a love” (145). Although the first sentence appears to invite the reader’s sympathetic approval, the second seems to go just a little too far, and wickedly to invite us to judge the situation from a more rational perspective—that of a narrator who does not cohere with the character’s viewpoint. The writing is a subtle exposé of deluded egoism.

A similar commentary can be applied to the language used about Camille after she has pushed the cat off the balcony: “A poor little murderess meekly tried to emerge from her banishment, stretched out her hand, and touched the cat’s head with humble hatred.” (132). “He lowered his head, imagining the attempted murder.” (140) “Thrown from the height of nine stories,” Alain thought as he watched her. “Grabbed or pushed. Perhaps she defended herself…perhaps she escaped to be caught again and thrown over. Assassinated.” (148-49) Perhaps we are on Alain’s side as he imagines Saha’s struggle for life. However, the last word, “Assassinated,” surely goes too far, and reminds us that after all it is a cat, and not a human being that is being referred to. Once again, our sympathy suddenly runs up against a sense of proportion, confronts reality.

(ii) Alain’s Home

(Much of this discussion is indebted to Marianna Forde’s article, “Spatial Structures in La Chatte” which I recommend to you. Forde discusses binary oppositions associated with Alain and Camille: down/up, closed/open, static/dynamic, past/future, old/modern, noble/common, living/dead.

1. Garden

The garden in suburban Paris at Neuilly is low down, five steps lower than the house branch. Forde considers in depth the significance of Alain’s association with the earth, with low places such as the garden and the house, the worn old servants, who are half-buried in their basement (105), and Camille’s contrary associations with height and open spaces. The garden is not usually presented in positive terms, but is associated, as in the first description (64) with blackness, or dark green, with fossilisation (calcined twigs), and old age. An iron fences walls it off from the real world (68). Far from being a place of fruition, the garden is presided over by a dead yew tree, which is mentioned no fewer than four times. Yew trees traditionally grow in cemeteries. Forde points out that a long hanging cluster of the poisonous laburnum hangs directly in front of Alain’s window (69). She suggests that the garden is in fact poisonous to Alain, because, like his attachment to Saha, it contributes to the stunting of his emotional growth. It protects him from the full gamut of adult experience. The prevalent colours of the garden are dark green and black. When colours other than these are associated with the garden, the effect is not so enchanting (145, bottom).

Other negative associations are with over-cultivation and over-civilisation, not in a good sense: “the secret exhalation of the filth which nourishes fleshy, expensive flowers” (90). There’s a sense of fossilisation, of the same summer scenes being acted and re-enacted again and again (92). The garden is also associated with age: “One of the oldest climbing roses carried its load of flowers, which faded as soon as they opened” (95). At his breakfast of “liberation” Alain receives “an ill-made, stunted little rose” (147).

2. Servants

There is a repetitive emphasis on the age of the servants, Emile the butler, and Juliette, the Old Basque woman with a beard. The physical descriptions of these are always negative, e.g., “The old butler muttered answers as shallow and colourless as himself” (94); “he raised his pale, oyster-coloured eyes, which had never laughed in their life, to the pure sky” (94).

3. Alain’s Room

The theme which merges most strongly in the depictions of Alain’s room, and himself in it, is his undeveloped childishness, his adolescence which is continuing into his twenties. The connections made between Alain and childhood, adolescence and childishness are innumerable in The Cat. When Alain reaches his room, he examines his face in the mirror, in a passage which demonstrates his self-obsession, if not narcissism (70). The box of ancient childish treasures, “bright and worthless as the coloured stones one finds in the nests of pilfering birds” (69), which he refuses to discard likewise suggests his refusal to let go of the past, a comment follows on his life as an only child (top of 70). At the end, when Alain returns to the setting of his pampered youth, his mother welcomes him by treating him again like a child (bottom of 149), and the old servants fall again into the patterns of a lifetime by serving “Monsieur Alain.” There is however restraint and a certain perceptiveness in his mother’s reaction, especially in her knowledge that a man has to be born many times with no other assistance than that of chance, of bruises, of mistakes (150-51). Like Alain, she nevertheless condescends to Camille as a member of the middle classes, classes that are only partially redeemed by their wealth (151).

Camille

It is important to distinguish between the information which the narrator reveals about Camille and Alain’s judgmental and resisting responses. That we as readers are invited to judge Alain for his judging of Camille seems plain from one of the early descriptions, in which it becomes clear that Alain prefers the shadow to the flesh-and-blood woman (65):

Unclasping her hands, the girl walked across the room, preceded by the ideal shadow… ‘What a pity!’ sighed Alain, Then he feebly reproached himself for his inclination to love in Camille herself some perfected or motionless image of Camille. This shadow, for example, or a portrait or the vivid memory she left him of certain moments, certain dresses” (65-66).

At this point, Alain is in a typically lowered, static state, watching Camille, who is dynamically moving about.

When Alain selects a photo of Camille for his bedroom, it is one “which bore no resemblance to Camille or to anyone at all” (74). The photo is of someone with accentuated features, “her painted mouth vitrified in inky black” (74). You should notice that this does not accurately describe the physical Camille. Camille’s make-up is not presented as hardening her or making her brittle. On the contrary, there is approval implied, both of her manner of self-presentation and of her body itself. Alain breathes in , “under a perfume too old for her, a good smell of bread and dark hair” (68). “Made-up with skill and restraint, her youth was not obvious at the first glance” (81). Cf. Also 95. “She was looking pretty every evening at that particular hour; wearing white pyjamas, her hair half loosened on her forehead and her cheeks very brown under the layers of powder she had been superimposing since the morning” (100). The vivid colours of life are captured (101) in the description of Camille laughing as she eats the melon. Alain detects, “how vivid a certain cannibal radiance could be in those glittering eyes and on the glittering teeth”; but this reaction opposes the other part of the description, and the reader is not obliged to agree. On the contrary, what the make-up does imply, is Camille’s wish to be attractive and pleasing to Alain. Cf. 85. In fact, her longing that he will love her spontaneously is obvious in almost every encounter, and in every encounter he hangs back.

Alain’s dislike of Camille’s natural and uninhibited sexuality, his repugnance at her parading around in the nude is undercut by the subtle revelations which are given, twice at least, that he has had mistresses in the past. The scene of the morning after their wedding night (83) is a none-too-subtle revelation of Alain’s judgmental snobbery: “She’s got a common back…She’s got a back like a charwoman.” Such comments are juxtaposed with Colette’s positive presentation of Camille’s physical grace: “But suddenly she stood upright again, took a couple of dancing steps and made a charming gesture of embracing the empty air.” Lightness and airiness typify descriptions of Camille. Alain’s sense that Camille is becoming fat while he becomes thinner by lovemaking is presented, significantly as the “age-old misogynist complaint.”

The Wedge

While Alain is at home on and below the ground at Neuilly, the airiness of the Wedge, a modern apartment on the ninth floor of a building called Quart-de-Brie is associated with Camille. The obvious triangular symbolism of the Wedge, with the tops of the three dying poplar trees visible outside (101), an indication perhaps of the ménage à trois formed by the two humans and the cat, is typical of the subtle symbolism operating throughout The Cat. The Wedge is open to breezes, which are never still (93). While Camille enjoys its openness to the elements, Alain tends to hole up there, especially in the little annex where he sleeps on the hard narrow bed, “the waiting room bench.” He brings in the pot plants to protect them from the wind.

The fireworks watched from the Wedge (135-37) may symbolise the brilliance and transience of Alain and Camille’s love. Despite the orgasmic connection, I think that the rockets are more closely connected with Camille’s unhappiness as she realises the hopelessness of her relationship: “It never lasts long enough,” she said plaintively (136). “No. It’s you. It’s you who… who don’t love me” (137). If we’re tempted to condemn Camille as the attempted murderer of the cat, it’s scenes and words of hers such as these that we should look at. In fact the near-homicide of the cat was the culminating act in Camille’s attempts to save her marriage, attempts that typify all her interactions with Alain from the very beginning. It’s a big and energetic act, which contrasts strongly with Alain’s predictable horror and condemnation. Consider the ridiculous over-statement on 155, “A little blameless creature etc….”

After she arrives at the Wedge, Saha follows Alain in avoiding the winds, though, like Camille, she passes her time watching from the balcony and shows no fear of heights. The culmination of Alain’s reaction against the Wedge comes in his fear of the storm. He seeks Camille’s protection, but characteristically withdraws when the storm is over. Few of us indeed get through life without facing storms, a truth that it would profit Alain to keep in mind.

Discussion Topics

1.Discuss the possible significance of eyes, dreams, gardens, the number three. Any other symbols?

2.Which does Saha most resemble – Camille or Alain? Or is it that they resemble her? (Which is primary?)

3.Discuss Saha as “character” and as symbol.

4.How do you feel about Camille’s attempted murder of Saha?

5.Discuss the representation and significance of subsidiary figures in The Cat, e.g. the parents, especially Alain’s mother; and the servants.

6. What feminist assumptions do you find in The Cat? Or, does the novel invite the reader’s sympathy for Alain? What, if anything, is unappealing about Camille?

7. Assuming that they are symbolic, what light do the roadster and the rockets cast on the contrasting characters of Camille and Alain?

8. Discuss ambiguity in The Cat.

9. Discuss The Cat as a despairing comment on heterosexual connection.

Colette’s The Cat: Selected Studies

Callander, Margaret M. Le Ble en herbe and La Chatte. Critical Guides to French texts. London; Valencia : Grant & Cutler; Artes Graficas Soler, 1992.

Davies, Margaret. Colette. Writers and Critics. Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd, 1961. [The Cat 85-89]

Dormann, Genevieve. Colette: A Passion for Life. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984. [Colette in pictures!]

Forde, Marianna. “Spatial Structures in La Chatte.” The French Review: Journal of the American Association of Teachers of French, Champaign, IL (FR). 58:3 (1985): 360‑367.

Hawthorne, Melanie. “’C’est si simple… C’est si difficile’: The Ideological Ambiguity of Colette’s La Chatte.” Australian Journal of French Studies (AJFS). 35:3 (1998): 360‑68.

Ladimer, Bethany. “Moving Beyond Sido’s Garden: Ambiguity in Three Novels by Colette.” Romance Quarterly, Washington, DC (KRQ) 36:2 (1989): 153‑167.